Black women graduate students enroll in higher numbers at for-profits

For-Profit Graduate Schools Popular With Black Women

Consumer advocates are concerned by the relatively large proportion of black women graduate students who attend for-profits.

July 25, 2017

“Of black bachelor’s degree recipients, women will more significantly go on to get master’s degrees,” said Sandy Baum, a senior fellow in the education policy program at the Urban Institute. “African-American women are more likely to go to the for-profit sector.”

Overall, African-American men and women are overrepresented at for-profit master’s degree programs. While accounting for 9 percent of the nation’s mix of college students, in 2007 they comprised a roughly a quarter of the for-profit sector’s graduate enrollment, according to Baum, who cited a report she co-authored.

And the numbers of black women who choose for-profit graduate education have increased slightly. In 2007, 24 percent of black women graduate students chose to pursue their degrees at for-profit institutions, Baum said, according to federal data. In 2014, 31 percent of black women graduate students were enrolled in for-profit colleges compared to 13 percent of all female graduate students and 9 percent of white women graduate students, according to an analysis of federal data by Elizabeth Baylor, the former director of postsecondary education policy at the Center for American Progress.

Total graduate student enrollment at for-profits decreased by more than 7 percent from 2015 to 2016, to 263,498 students, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

For critics of the sector, the higher proportion of African-American women enrolling in for-profit master’s programs is an issue.

“This trend is concerning because for-profit graduate education is a relatively new sector and its results are unknown,” Baylor said in an email. “Generally people pursue advanced degrees because they are associated with higher lifetime earnings and better job security. However, policy makers and the public don’t know if that is, in fact, true for people who attend for-profit colleges.”

Graduate institutions don’t have to report completion rates to the federal government, she said, or break out student loan repayment rates by level of education or loan program.

“While it may be true that attending for-profit colleges might not be good because of student debt and poor outcomes, the outcomes depend on what majors are being pursued,” said Anthony Carnevale, a research professor and director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

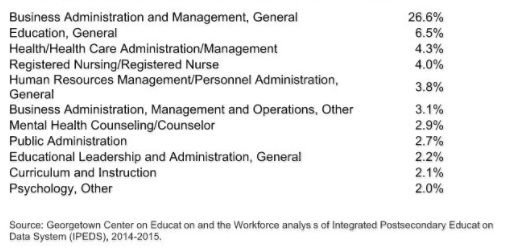

According to an analysis by Carnevale, the most popular major among black women who enroll in for-profit graduate degree programs was business administration and management, at 27 percent.

Meanwhile, the median earnings for black women with graduate degrees from any institution are $60,000 for business majors and $50,000 for education majors, according to the analysis.

Baum said the decision to pursue a for-profit graduate degree could be driven by convenience, since these are degree programs that also exist at public institutions.

“The reality is that master’s degree programs by their nature enroll higher proportions of women, blacks, students from lower-income backgrounds and people who earn bachelor’s degrees at older ages,” said Steve Gunderson, president and chief executive officer of Career Education Colleges and Universities, the primary trade group for the for-profit sector. “The reality is that many of the master’s degree programs do not pay as well as those professional degree programs do as you get into those careers.”

Gunderson used graduate degrees in education as an example, noting that K-12 teachers typically earn a master’s degree, which improves their skills but doesn’t put them in a higher salary range.

“One thing our sector is proud of is that we meet students where they are in daily life,” Gunderson said. “We’re much better at scheduling academic programming in ways that work with their schedule that often includes full-time jobs or children, and that has a big impact on whether they attend a traditional graduate program.”

Some traditional graduate programs instead pride themselves on exclusivity rather than access, he said.

The flexibility also benefits employers who want their employees to continue working, said Baylor, but may offer a raise or promotion if the employee pursues a master’s degree.

“Sure, you can say they chose this and they have bachelor’s degrees, so they’re in a good position to make this decision,” Baum said. “But given the history of for-profit institutions — the prices, debt levels associated with them and history of credibility in the labor market — you have to at least question why this is a good decision for this group and not others.”