Feds’ data error inflated loan repayment rates on the College Scorecard

College Scorecard Screwup

Final Friday release by the Obama administration’s Education Department corrects a substantial error in loan repayment rates on consumer web tool.

The U.S. Department of Education has fixed a mistake in the data for its College Scorecard that substantially inflated loan repayment rates for most colleges.

On the last Friday afternoon of the Obama administration, the department issued a statement describing the “coding error” that led to the undercounting of borrowers who failed to pay down any of their undergraduate student loan balance.

The erroneous repayment rates appeared in the College Scorecard — a consumer tool the feds released in 2015 in lieu of a failed effort to create a college ratings system — and in a data attachment to the Financial Aid Shopping sheet.

“After discovering the coding error, the department worked to get accurate, refreshed data out as soon as possible, not waiting until the next annual Scorecard update to do so,” wrote Lynn Mahaffie, a veteran department official. “To ensure we’d gotten it right, we added a number of quality assurance activities and reran some of the tests we’d done before, testing the applied software logic and revised rates, and benchmarking the rates against other available data.”

Observers gave the department credit for fixing the mistake before the Trump administration takes over, but some said the embarrassing flub shows the difficulty of what the White House has tried to do with accountability through data. The department defended its Scorecard, saying the web tool provides more and better data for students and families than was previously available.

The coding error does not affect any other department-calculated loan repayment rates and should not have an impact on other calculations on the Scorecard.

Higher education advocacy groups and lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have called for the feds to rely more heavily on loan repayment rates than on default rates as a higher education accountability metric. They argue that colleges should be judged on whether students they educate are able to make progress paying down their debt, rather than just tracking percentages of borrowers who default.

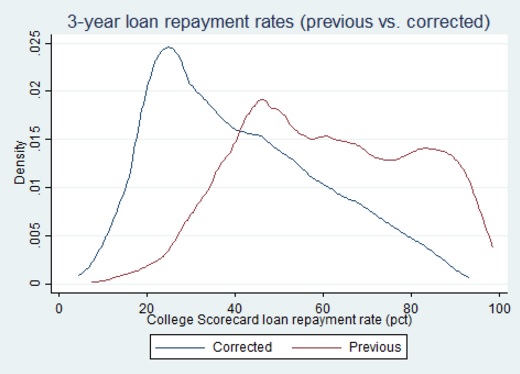

The Scorecard’s repayment rates, however, offered a distorted picture before the newly made fix. Several experts who crunched the numbers found a roughly 20 percentage point decline in the overall national rate.

“It turns out that the changes in loan repayment rates are very large,” Robert Kelchen, an assistant professor of higher education at Seton Hall University, wrote on his blog. “Three-year repayment rates fell from 61 percent to 41 percent; five-year repayment rates fell from 61 percent to 47 percent; and seven-year repayment rates fell from 66 percent to 57 percent. These changes were quite similar across sectors.”

Source: Robert Kelchen

Also crunching the numbers and finding similarly large corrections were Kim Dancy, a policy analyst with the education policy program at New America, and Ben Barrett, a program associate there.

“The new data reveal that the average institution saw less than half of their former students managing to pay even a dollar toward their principal loan balance three years after leaving school,” they wrote in a blog post. “Even more borrowers are not making progress on their loans than previously thought.”

The department’s error had less of an impact on repayment rates across longer time horizons, Dancy and Barrett said, meaning the corrected rate dropped less for borrowers who entered repayment seven years ago than for those who entered three years ago.

Besides older cohorts of borrowers having more years in the work force to make payments, they wrote that perhaps increasingly popular income-driven repayment plans are allowing newer cohorts to make lower payments on their student debt that don’t drive down the principal of loans.

The department said the coding mistake did not substantially affect how colleges stack up against one another on repayment rates.

More than 90 percent of institutions on the Scorecard did not move away from their previous repayment-rate standing as being either above or below average, or roughly at the average mark, according to the department.

As Kelchen noted in his blog entry, the department also last week announced that it was expanding publicly available student aid data in an effort to increase transparency. The new access should help researchers spot discrepancies in federal data sets, the department said.

In the meantime, Kelchen said the coding fix makes a big difference in the picture the Scorecard paints about the number of borrowers who are making at least some progress repaying their federal loans.

“This change is likely to get a lot of discussion in coming days,” he said, “particularly as the new Congress and the incoming Trump administration get ready to consider potential changes to the federal student loan system.”