Ideas for improving higher education’s primary role in work force development

Better Marriage Between College and Job Training

By Paul Fain

March 22, 2017

The administration has said too many students are being prodded toward bachelor’s degrees over apprenticeships and other noncollege options.

“We must embrace new and effective job-training approaches, including online courses, high school curriculums and private-sector investment that prepare people for trade, manufacturing, technology and other really well-paying jobs and careers,” President Trump said last week during a meeting on vocational training with U.S. and German business leaders.

“These kinds of options can be a positive alternative to a four-year degree,” he said. “So many people go to college, four years, they don’t like it, they’re not necessarily good at it, but they’re good at other things, like fixing engines and building things.”

Likewise, many in higher education, mostly at four-year institutions, resist pressure for colleges to be more attuned to their occupational role, arguing in defense of general education and decrying the transactional view of college as being primarily a means to a job.

College and faculty leaders also tend to dislike performance metrics that are based on graduates’ employment and earnings.

Yet higher education has been the federal government’s primary work force system for decades. And that is unlikely to change, experts said.

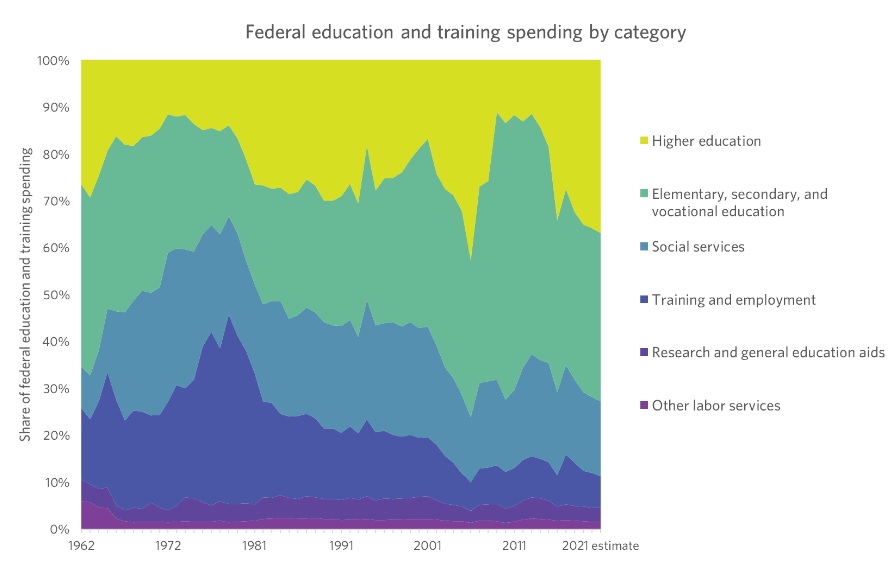

Just 6 percent of the roughly $114 billion the federal government spends annually on work force development and education goes toward noncollege job-training programs, according to data from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce. (See graphic, below.)

Higher education gets a much larger share of that funding — roughly 34 percent — with K-12 receiving a similarly large portion. Source: Georgetown U Center on Education and the Workforce

Source: Georgetown U Center on Education and the Workforce

“We’re spending more on job training than ever before. It’s just that the funding has moved to education,” said Mary Alice McCarthy, director of the Center on Education and Skills with the education policy program at New America and a former official at the U.S. Education and Labor Departments.

This was not always the case. Anthony Carnevale, the Georgetown center’s director, said job training and employment programs outside higher education and K-12 accounted for 40 percent of the federal work force budget in 1978.

One reason for the shift is that at least 60 percent of jobs now require at least some college education, according to the center, up from 28 percent in 1973. The trend will continue, Carnevale said.

In addition, federal spending on higher education is an easier political sell than paying for occupational or vocational programs that train workers outside college.

“It’s not the thing middle-class people want for their kids,” said Carnevale.

So higher education became the preferred system for job training, he said, a trend that began in the 1980s and accelerated during the Clinton administration, which shuttered federal job-training programs in exchange for higher education subsidies aimed at the middle class. (Employers spend $177 million a year in formal job training, the center has said, an amount that is increasing, but less quickly than overall spending on higher education.)

“Higher education became the chicken in every pot,” said Carnevale. “It moves votes.”

‘Time for a Reboot’

Yet nobody seems particularly happy about the federal government’s current approach to job training.

Bipartisan angst about the skills gap has become more urgent, as employers say they struggle to hire work-ready employees. Meanwhile, a wide range of experts said noncollege federal work force programs are inefficient, duplicative and lacking in incentives.

The current $18 billion annual federal work force budget is divvied up among roughly 50 programs.

“It’s spread across a wide range of programs for niche audiences,” said Jason Tyszko, executive director of the Center for Education and Workforce at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, who describes federal work force programs as being “stretched thin.”

The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), which was enacted in 2015 and replaced an outdated predecessor law, is the largest of the federal job-training programs. Its $3.4 billion annual budget is intended to extend across education, training and job-support services, with a goal of helping job seekers and employers as well as setting priorities for local, state and regional work force investment priorities — a big ask.

The program’s task won’t get easier, at least if the Trump administration’s budget plan takes hold in the U.S. Congress.

The White House has called for a $2.5 billion, or 21 percent, cut to the Labor Department’s $9.6 billion in annual funding. While Trump’s budget document was relatively light on details, the National Skills Coalition projected that it would result in as much as a 50 percent cut to WIOA’s budget.

The White House plan also would decrease “federal support for job training and employment service formula grants, shifting more responsibility for funding these services to states, localities and employers.”

A broad coalition of work force and labor groups criticized the proposed cuts, calling them unnecessary and inconsistent with the Trump administration’s job-creation goals.

But Tyszko, citing two 2011 Government Accountability Office reports that described wasteful overlap and fragmentation of federal work force programs, said funding levels aren’t the main problem.

“Throwing more money at these programs and how they run could actually have diminishing returns,” he said.

Likewise, a broad range of experts agreed with Tyszko that the time is ripe for the federal government to reconsider its approach to occupational training.

“There really needs to be a fundamental reconciliation between higher education and work force development,” said Maria Flynn, president and CEO of Jobs for the Future and a former official with the Labor Department’s Employment and Training Administration.

Better coordination between the Labor and Education Departments is needed, she said, with particular attention to the interplay between WIOA and the Pell Grant program, which is the primary federal grant for low-income students. (The Trump budget would cut $3.9 billion from the Pell program’s reserves.)

There are some signs that the two systems are being steered together, Flynn said.

For example, she cited a bipartisan legislative proposal in the U.S. Senate that would allow students to use Pell Grants for short-term job-training credentials, such as college-issued certificates. Currently Pell can be applied only to programs that take more than 15 weeks or 600 clock hours to complete.

Other promising ideas Flynn mentioned include an Education Department experiment that is granting temporary access to federal financial aid for noncollege training entities, including skills boot camps and online course providers, under partnerships with accredited colleges on job training in high-demand fields.

Likewise, Flynn said the college and career pathways approach championed by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the American Association of Community Colleges can help students follow a more structured route to completion and a job.

Structured pathways share some resemblance to the German model of nudging students toward an occupation earlier in their academic career, she said, without the controversial student “tracking” that’s a tough sell in this country.

“In the U.S. there’s some middle ground we can get to,” she said, “by really emphasizing the idea of pathways.”

Likewise, McCarthy and others said the federal government could do more to prevent students from having to spend more time and money than is necessary on vocational training.

Perverse incentives, she said, encourage colleges to make academic programs credit bearing and longer than might be ideal. For example, some medical assistant and early childhood programs were noncredit in the past. But to make those offerings financially viable, McCarthy said, many community colleges and for-profits began offering credit-bearing options in those fields.

One overarching fix to the lack of coordination on job training, according to McCarthy, would be for some Labor Department programs to be folded into Congress’s looming reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, which is the law that oversees federal aid. She said that shared focus could benefit college-based occupational training, too.

“We have to bring what we know about good training quality to the higher education side,” said McCarthy. “It’s definitely time for a reboot.”

Market for Apprentices

Apprenticeships in particular appear to be in vogue as the GOP dominates both federal and state policy making.

The president and Ivanka Trump, his daughter, met last week with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and a group of corporate executives from the U.S. and Germany to discuss vocational training. Ivanka Trump said the executives would form a task force that would produce a report on training programs that should be expanded.

President Trump reportedly has embraced a call by one of those executives to create five million apprenticeships within five years. That would be a steep increase from the current number of apprentices — roughly 450,000 — who are enrolled in Labor Department-registered programs, according to McCarthy.

The White House has pushed for private funding for apprenticeships and job training, with Ivanka Trump reportedly saying last week that “ingenuity, creativity often comes from the determination of the private sector.” And last year Congress added $90 million in funding for apprentice programs.

The Trump budget says it will help states expand apprenticeships, although it doesn’t specify new money for them. But the $1 trillion in infrastructure spending the White House has said it is mulling probably would include funding for apprenticeships and other job training. (Carnevale’s center projects that 55 percent of jobs created under such a program would not require any college, with 60 percent of new infrastructure jobs requiring no more than six months of on-the-job training.)

Some observers said the current structure of the Labor Department’s apprenticeship program can be balky. To participate, companies often must file voluminous applications and wait months for the feds to respond.

“It’s a bureaucratic process where those who are good at filling out papers get the funds,” said Ryan Craig, co-founder of University Ventures, an investment firm. “Government is ill positioned to pick winners.”

As a result, Craig is focused on job-training “intermediaries” between colleges and employers, where the money comes from job seekers or from employers themselves. Examples include Revature, an employer-funded training firm, and boot camps like Galvanize and General Assembly.

Yet there’s a role for government in promoting apprenticeships, Craig said.

He cites the United Kingdom’s apprenticeship levy, which goes into effect next month. The U.K. is requiring all employers with an annual payroll of more than 3 million pounds ($3.74 million) to pay a tax of 0.5 percent of their payroll amount on apprenticeships, with the government kicking in an extra 10 percent “top-up” to those apprenticeship funds.

Craig called the levy an exciting idea, which, if combined with the right incentives and outcomes requirements, would be worth a look in this country.

“We need to figure out how to spawn a market here,” he said.