Default Crisis for Black Student Borrowers

Inside Higher Ed

Default Crisis for Black Student Borrowers

Half of all black students who took out federal student loans defaulted in 12 years, according to two analyses of new federal data on student borrowers.

October 17, 2017

Earlier this month the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics published a report on patterns of student loan repayment for two groups of borrowers who first enrolled in college in 1995-1996 and in 2003-2004.

Historically the department has not collected much data on student debt that can be broken out by the race or ethnic background of borrowers. The new report, however, included tools that researchers can use to compare how various groups are faring.

Two resulting analyses found a troubling picture for black students who take out loans.

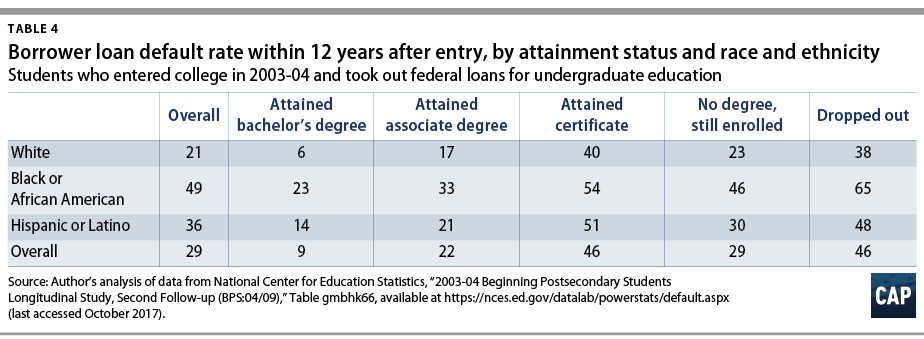

Nearly half (49 percent) of all black borrowers in the 2004 group defaulted on at least one loan within 12 years, wrote Robert Kelchen, an assistant professor of higher education at Seton Hall University. That default rate was more than twice that of white students (20 percent) and more than four times the rate of Asian students (11 percent).

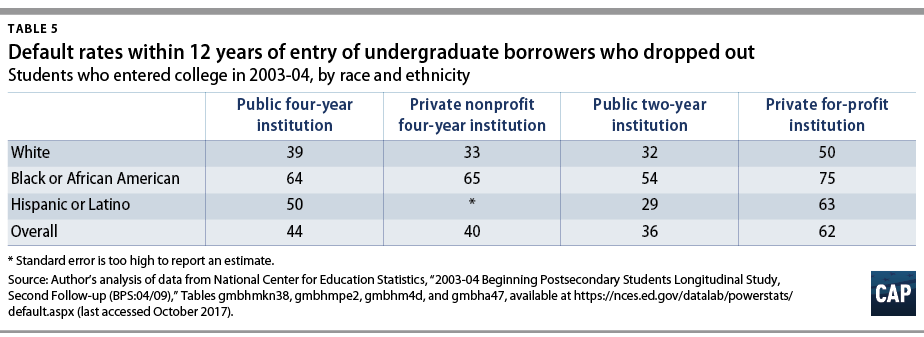

“The differentials are still present across sector, with more than one-third of black students defaulting across all sectors while a relatively small percentage of Asian students defaulted across all nonprofit sectors,” Kelchen said. “Default rates at for-profit colleges are high for all racial/ethnic groups, with almost half of white students defaulting alongside nearly two-thirds of black students.”

The Center for American Progress on Monday released a report on the new numbers.

The federal data show that the typical black student who enrolled in 2004 and took on debt for an undergraduate education owed more on their student loans after 12 years than the amount originally borrowed, found Ben Miller, the senior director for postsecondary education at the center and a former department official during the Obama administration.

Likewise, 75 percent of black borrowers who failed to complete at a for-profit institution ended up defaulting, Miller said. And he said that disturbing figure could be even worse for black students who enrolled at for-profits during the sector’s peak, which was in the recession’s wake.

Default rates for students who dropped out before completing generally are high. But black students fared worse than their peers.

Miller’s analysis shows that 50 percent of white students who enrolled at for-profits but dropped out later defaulted, compared to 39 percent of white noncompleters who began at a public four-year institution. But 64 percent of black students who failed to complete at a public university ended up defaulting, compared to 50 percent of Hispanic or Latino borrowers.

Likewise, even black students who earned a bachelor’s degree were substantially more likely to default. Just 9 percent of all borrowers who earned a bachelor’s defaulted, on average, Miller said. Yet almost one-quarter (23 percent) of black bachelor’s-degree earners defaulted.

The default rates for black borrowers were worse than those for Pell Grant recipients over all, which Miller said means the results for black students cannot be attributed solely to lower average income levels.

Black students also were more likely to borrow, according to the new data. For example, Miller said 62 percent of black students who attended a community college took out a federal loan, compared to 46 percent of white students and 40 percent of Hispanic or Latino students.

“Seeing even African-American students who earned a bachelor’s degree struggle also reinforces that we cannot pretend the federal student loan program exists in a vacuum,” Miller wrote. “The median African-American household has just $1,700 in accumulated wealth. Racial discrimination in hiring has not improved over the past quarter century.”

Part of the solution to the serious, complex problem of default among black student loan borrowers is for the department to start collecting data on the race and ethnicity of borrowers, he said, adding that the feds should review completion, repayment and default rates to identify colleges with sizable gaps.

Likewise, he said states and colleges should consider if their policies might be driving more black students to borrow. One possible example could be well-meaning admissions practices that divert black students to colleges with less money to pay for grant aid.

“Perhaps it’s too much to expect student loans and postsecondary education to solve these structural problems,” wrote Miller, “but sending African-American students into an inequitable adulthood with large debts from college can put them even further behind than they already start.”