Education Department on track to update College Scorecard

Transparency With Staying Power

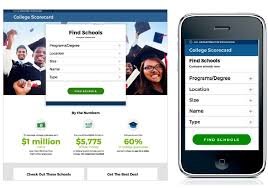

The Department of Education appears ready to update the College Scorecard later this year.

The Department of Education appears to be planning to keep around one of the most high-profile higher ed initiatives of the Obama administration.

Department staff are taking steps to update the data feeding the College Scorecard, a tool that allows prospective students to look at measures like the debt burden of an institution’s graduates, by September of this year, according to higher ed groups. That would be counted as a victory by proponents of more transparency in higher ed, even though the Scorecard wasn’t among the Obama efforts the Trump administration promised to eliminate.

Some have wondered about the longevity of the Scorecard, since it wasn’t required by law and isn’t so established that it would be difficult to abandon.

Maintaining the tool for now may have as much to do with the timeline — collecting and validating the data is a months-long process — and low level of staffing in the department as it does with any clear strategy from the administration. But with another year in the books, it could become more likely that Education Secretary Betsy DeVos keeps the tool long term while putting her own stamp on the interface.

The Scorecard was first published in 2015 after a process that began with a much more controversial proposal from the Obama administration to rank institutions. Colleges and universities have had concerns, but some higher ed groups have come on board with the final product, which allows students and researchers to find information about outcomes without attaching accountability. Community colleges have complained that the Scorecard doesn’t count many of their students, and liberal arts institutions have criticized the data choices, saying that they devalue the kind of education their institutions provide.

But the website has been widely used over the last two years, said Michael Itzkowitz, a senior policy adviser on higher education at Third Way who previously worked on the Scorecard at the Department of Education. At least two million individual users have accessed the site and 100,000 students have done so in the last 30 days, he said.

Academics and researchers have downloaded Scorecard data for analysis. And more than 600 developers have also used the Scorecard application programming interface to create their own search tools.

“Assuming they continue to make progress, it will be gratifying to see that they value transparency and better information on college outcomes,” Itzkowitz said. “A lot of people are very invested in the College Scorecard tool itself — not just for the website but for the data it provides.”

Jamienne Studley, former under secretary of education, said the department developed the Scorecard at a time when many parallel efforts were shedding more light on outcome and results.

Higher education institutions across the board strongly rejected the idea of ranking colleges and universities. Studley, now a consultant and the national policy adviser at Beyond 12, said after listening to the response from college leaders, the Obama administration achieved a result that avoided “really corrosive” methods of comparing institutions.

Some higher ed groups still have gripes with the data presented on the Scorecard, arguing that the tool doesn’t accurately reflect their student populations or sometimes just has incorrect data.

Tim Powers, director of accountability and regulatory issues at the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, said some NAICU members have been frustrated by the amount of time it has taken to have incorrect information updated on the site.

Jeff Lieberson, a spokesman for the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, said the group has not discussed the Scorecard with the Trump administration, but it will be on APLU’s agenda for future talks. The group has pushed to have data from the Student Achievement Measure, which tracks student movement across higher ed institutions, to the site.

“The department pledged to include it, but it never happened in the previous administration,” he said. “We think it’s critical for that data to be included.”

Clare McCann, another former Department of Education official, said some objections to Scorecard data could only be addressed by the creation of a student unit record system. The data don’t, for example, include outcomes for students who did not receive Title IV aid.

“The biggest concerns can only be addressed by Congress,” she said.

For now, it appears that the most time-consuming work on the Scorecard — collecting the data — is going ahead without any significant changes by the department’s leadership. Certain pieces of information such as closed institutions are updated more regularly. But updating the full website is a complex process requiring multiple steps.

Because there is no single data set of student outcomes, the department must submit cohorts of students to the Department of Treasury with multiple privacy protections built in along the way. Treasury returns aggregate data on earnings and student debt levels for each institution in the Scorecard. That process incorporates federal data from three different sources: the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, the National Student Loan Data System and the Treasury.

The timeline for the department usually begins in winter for an update by September.

A department spokeswoman declined to comment on what intentions the administration has for the Scorecard, saying there are no plans to change it and no plans not to change it.

With staffing levels still low and a number of deadlines looming for decisions on Obama-era regulations like gainful employment and borrower defense, the Scorecard likely ranks low on the list of priorities. McCann said because the tool is basically consumer information, it wouldn’t rank on the same level as accountability measures the department may look to address by rewriting regulations.

The Obama administration saw the Scorecard as a tool that would continue to evolve and be improved. DeVos could look to put her own stamp on the site, possibly reflecting additional feedback from the institutions it measures.

“It’s probably too soon to say whether or not in the long term they continue to recognize the value of this data and continue to publish the Scorecard or some version of it,” McCann said. “It’s a good sign for now.”