Investors Think For-Profit Colleges Have a Bright Future Under Trump – Bloomberg

-

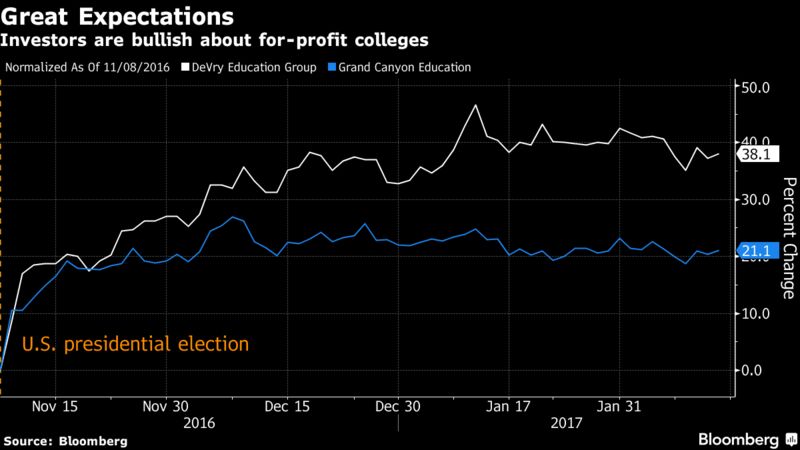

DeVry, a for-profit education leader, has jumped about 40%

-

The bet: Trump will reduce regulations after Obama crackdown

The invitation went out to top universities including Ohio State and Notre Dame: Let’s talk about the future of American higher education under President Donald Trump.

It’s quite a turnabout for a company that, not long ago, seemed to exemplify the problems in for-profit classrooms: Students tend to graduate with more debt and fewer job prospects than those who attend traditional schools. In recent years, scandals and bankruptcies have jolted the industry and sent students — and investors — running.

On the heels of the Trump U. settlement, DeVry agreed in December to a $100 million settlement of a federal lawsuit alleging it mislead people about its students’ job success. As usual in such cases, neither Trump nor DeVry admitted to any wrongdoing.

Now, the shift is palpable. Trump’s new education secretary, the wealthy Republican fundraiser Betsy DeVos, has long supported directing taxpayer dollars to schools run by for-profit companies, including those operating fully online — an approach pioneered by publicly traded higher-education businesses. That’s good news for them because they rely on federal student loans and grants for as much as 90 percent of their revenue.

“We are encouraged,” said Lisa Wardell, Devry’s chief executive officer. “We’re looking for a voice and a seat at the table.”

Bullish Bets

DeVos, confirmed only after Vice President Mike Pence broke a 50-50 tie in the Senate, has largely focused on K-12 education. Now she will step into the national debate over the value — and soaring costs — of traditional colleges and universities.

Despite hard questions about their own value and cost, for-profit education companies are positioned to prosper in the Trump years, analysts say. Trace Urdan, a research analyst in San Francisco at Credit Suisse, upgraded DeVry to “outperform” the day after the November election. He expects Trump will take a friendlier approach than Obama, whose administration curbed funding to schools that failed to meet certain criteria, such as how much debt students shoulder relative to earnings.

Control Purse Strings

DeVos, 59, is married to the scion of Amway Corp., one of the world’s best-known multilevel marketing companies. She will control federal purse strings on higher education, overseeing the issue of $30 billion in Pell grants and more than $100 billion of student loans annually, as well as the collection of those loans.

Trump, meantime, plans to tap Jerry Falwell Jr., a campaign ally and president of conservative Christian Liberty University, to help examine how to get the government out of higher education altogether. Falwell, son of the fundamentalist preacher who founded the Moral Majority, said he would look at ways of reducing “overreaching regulation” in a Jan. 31 Chronicle of Higher Education story. He declined to be interviewed for this article.For-profit colleges generally don’t focus on traditional college students: recent high school grads on campus quads. Most DeVry students are over the age of 25 and many are veterans or working parents. Roughly a third are African Americans and Hispanics; two thirds are women.

‘New Normal Students’

“We’re serving the new normal students,” Wardell said. “These are students that don’t have the economic means to privately pay for school.”

Source: DeVry

DeVry’s most popular programs include medical billing, business administration and network-systems administration. The company also operates a nursing school, a veterinary school and Caribbean-based medical schools that train students who often failed to get into U.S. universities.

Wardell hopes the Trump administration will look at the “unintended consequences” of regulations such as Obama’s debt-to-earnings measure. The Department of Education classifies DeVry’s veterinary school as “in the zone” requiring improvement. DeVry thinks this is unfair because its default rate is low, and besides, “we need vets,” Wardell said. “It’s not that we don’t want to be regulated.”

The default rate “provides only a limited snapshot of one type of student-loan struggle,” said Ben Miller, senior director for postsecondary education at the Center for American Progress policy institute in Washington. For example, it tracks results only within three years of leaving school.

Wardell, who served on DeVry’s board before being named CEO last May, said for-profit schools have gotten a bad reputation because of a few bad practices.

Self-Policing

“If we had policed ourselves seven or 10 years ago as an industry, much like the financial-services industry has done,” she said, “we would not have found ourselves in the quagmire in which we found ourselves in the last few years.”

Wardell said DeVry is trying to hold itself accountable to students, adopting various commitments aimed at disclosing costs and potential career outcomes. It’s also reducing to 85 percent the maximum amount of revenue it will get from federal funds.

Of course, not everyone wants to see federal tax dollars channeled to for-profit education in the first place.

The promises of increased transparency are “steps in the right direction,” said Robert Shireman, deputy undersecretary of education under Obama and now a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank. “They don’t change the problematic dynamic of for-profit education: If we spend less on teaching, we have more money for shareholders.”