Survey finds increasing interest in skills-based hiring, online credentials and prehire assessments

Recent headlines have touted the move by several big employers to stop requiring new hires to hold college degrees. Meanwhile, a drumbeat of studies show increasing labor market returns for degrees, and employers say they value the critical thinking skills of liberal arts graduates.

These seemingly oppositional trends are both real and on display in a new report from Northeastern University’s Center for the Future of Higher Education and Talent Strategy. The report sheds light on a technology-enhanced shift in the way workers are being hired in the knowledge economy.

The traditional college degree remains by far the best ticket to a good-paying job, a well-established fact bolstered by a survey the center conducted. But the results also suggest that college leaders should pay close attention to the gradual, ongoing transformation of HR functions as well as to nascent changes in how employers view alternative credentials, particularly of the digital variety.

“The way employers relate to higher education is shifting,” said Sean R. Gallagher, the center’s executive director and the report’s author. “It’s employers getting savvier.”

The center surveyed 750 hiring leaders at U.S. employers in August and September. The results are nationally representative, spanning a wide range of industries and organizational sizes.

Most respondents reported an increase (48 percent) or no change (29 percent) in how they value educational credentials in hiring during the last five years. Just 23 percent reported a decline.

A majority (54 percent) of those surveyed agreed with the statement that college degrees are “fairly reliable representations of a candidate’s skills and knowledge.” And 76 percent agreed that completing a degree program is a “valuable signal of perseverance and self-direction” in a job candidate.

Likewise, 44 percent of respondents said the level of educational attainment required or preferred for the same job roles had increased over the last five years. Most who responded that way (63 percent) indicated that additional education requirements were due to evolving skills needed for jobs, rather than the mere availability of candidates with better credentials, a finding that argues against conventional wisdom on credential inflation.

In addition, 64 percent of respondents said the need for “continuous lifelong learning” in the future will drive demand for higher levels of education and more credentials.

While the traditional degree’s currency is secure for now, the survey found that employers increasingly are moving toward hiring based on applicants’ skills or competencies. And while it remains small, the market for nondegree microcredentials is growing rapidly, according to the survey.

The report points to the increasing use of data and analytics in hiring, noting that another study found 30 percent of HR departments reporting some form of analytics usage this year, up from 10 percent a few years ago.

As a result of the increasing reliance on artificial intelligence and analytics in hiring, the report predicted that employers are likely to change their preferences for credentials.

One area where this is happening is the rise of skills-based hiring that often de-emphasizes degrees and pedigrees. These typically technology-enabled strategies involve employers defining specific skills that are necessary for the job and seeking them in candidates. As examples, the report points to IBM’s New Collar Jobs project and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation’s Talent Pipeline Management Initiative.

The survey found that 23 percent of respondents are moving in this direction, with another 39 percent reporting that they are exploring or considering such a move.

Going Online and Micro

Online credentials have become mainstream, according to the report.

“Both the education market and the HR function are less digitized than many other sectors,” Gallagher said, pointing to finance and health care as examples. “It’s coming to education.”

The survey found that 71 percent of HR officials have hired someone with a degree or credential that the employee earned completely online. However, 39 percent of respondents viewed online credentials as being second class, saying they are generally lower quality than those completed in person. Yet more than half (52 percent) said they believe that in the future, most advanced degrees will be earned online.

That hunch is backed by data the Urban Institute released earlier this week about master’s degrees.

The rate of enrollment in online master’s courses or programs has increased substantially since 2000, the analysis found, and is more common than in bachelor’s degree programs. In 2016, the institute said 31 percent of students in master’s tracks reported that their program was entirely online, with 21 percent reporting that they took some online courses.

“You can’t ignore online,” Gallagher said.

The growth of digital learning options has spawned a variety of short, subdegree awards. These microcredentials include digital badges, MicroMasters from edX and Udacity’s Nanodegrees.

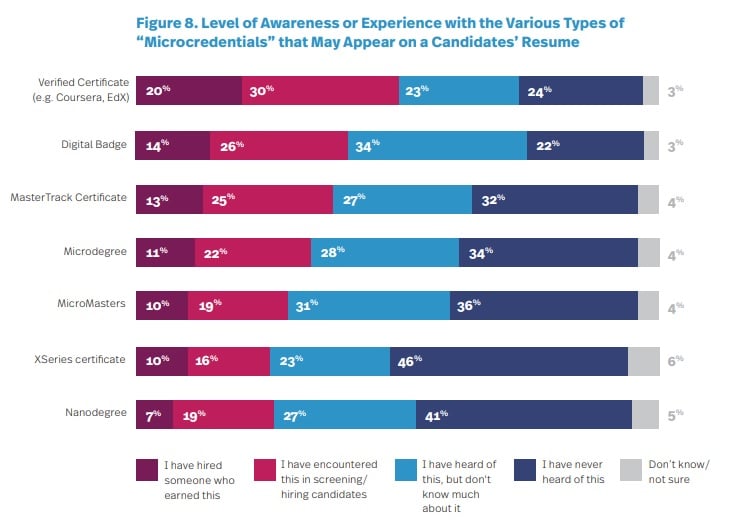

Awareness of these credentials in HR departments remains relatively low, according to the survey, yet still substantial. For example, 29 percent of respondents said they had encountered MicroMasters in the hiring process, and 10 percent said they had hired a candidate who had earned one. Another 36 percent said they had never heard of the credential from edX.

Microcredentials currently appear to be functioning as a supplement to degrees, the survey found. But that could change. A majority of respondents (55 percent) agreed with the statement that microcredentials are “likely to diminish the emphasis on degrees in hiring over the next 5-10 years.”

Test Before Hire

The biggest near-term challenge to the reliance on degrees in hiring, the survey found, is the use of prehire assessments such as online tests given to job candidates.

More than a third of respondents (39 percent) expect these assessments to have an impact on hiring within three years, and nearly 70 percent within five years.

Those findings build on a report Ithaka S+R released earlier this week in an attempt to map the “Wild West” of prehire assessment.

The report documented a “wave of rapid innovation” in this space. The interest is being driven in part by the perceived gap between job candidates’ competencies and employers’ needs, the group said, which in turn is contributing to a growing distrust by employers in “signaling credentials” such as college degrees, industry association endorsements and state licensures.

“We are at the early stages of a new market, a new industry,” said Martin Kurzweil, director of the group’s educational transformation program. Kurzweil co-wrote the report with Meagan Wilson, a senior analyst there, and Rayane Alamuddin, associate director for research and evaluation at Ithaka S+R.

As an essay published by Inside Higher Ed earlier this week noted, prehiring assessment faces regulatory and legal challenges in this country, including the risk of lawsuits alleging that such screening of hires is discriminatory. Yet plenty of experimentation with the practice is occurring, said Kurzweil.

The activity around prehiring assessment brings both promise and risks, he said. Kurzweil is excited about the prospect of “hiring people based on what they can do rather than their pedigree.” But the stakes are high, he said, particularly as profit-seeking companies move into the space.

The marketplace for prehiring assessments already is flooded, according to the report. Content and software across assessments and employers’ human resources systems often are incompatible. And higher education administrators and industry association officials tend to be out of touch with new methodologies used by employers and assessment providers.

The time is ripe for college leaders to play a role in shaping the use of prehire assessments, Kurzweil said, such as contributing to norms around how the tools are used.

“We think higher education should be more engaged in what’s happening,” he said. “This is a historical force that’s sweeping through. It’s going to happen.”